Who Was Zoroaster?

What little is known of Zarathustra biographically is gleaned primarily from the Zend-Avesta, the bible of Zoroastrianism, which Zarathustra is said to have authored. In this work, he is referred to under his family name of Spitama “white” as well as the name “Zaraϑuštra”, as written in his native language of Avestan. Documentation of this language is isolated to the Zoroastrian scriptures and the name appears to be derived from the Indo-Iranian for “He who can manage camels”, which was Zarathustra’s father’s vocation. The word, “Zaraϑuštra” is also thought to have been associated with the title of “chief” or “high priest”. The English (or Latinized) name “Zoroaster” is derived from a later translation.

Therefore, using the names “Zaraϑuštra”, Zarathustra, Zarathushtra, or Zoroaster are all correct and generally accepted equally among those who study him. The language of Avestan was associated with an area of the Middle East which currently corresponds with Afghanistan, some parts of Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, and Zoroaster has been associated most frequently with (and possibly born in) Bactria in the northwestern part of Iran, although his birthplace is still an article of much debate.

Although his followers celebrate his birthday on March 26th, there is no scholarly agreement upon an exact date–or even century–of his birth. Zoroaster, or Zarathustra, lived and produced the writing of his scriptures—the foundation of Zoroastrianism–somewhere between the 6th and the 18th Century B.C.–the later date due to the mention in an ancient Greek work which refers to Zarathustra as having been born “300 years before Alexander”. This time period was also when King Darius, the son of King Vishtaspa, who is mentioned frequently in the Gathas, is documented as having lived. Other scholars speculate that the later year is more accurate, as the language used in the Gathas, Gathic Avestan, bears many similarities to a version of the Sanskrit which dated from 1500-1200 B.C., an idea which some theorize does not negate the stipulation of the later birthdate, as often language used in sacred or poetic literature is different than the colloquial language of the day. The language issue has also been attributed to the concept that while Gathic Avestan was no longer used in conversation, it was still known and studied, similar to the way that Latin, while it is considered a “dead” language, is still studied and known among scholars. The debate continues. Zarathustra, son of Pourushaspa and Dugheda, was said to have experienced many miracles and brushes with divinity as a baby and throughout his childhood, although they were not recorded until centuries after his death. His mother was said to have been glowing throughout her pregnancy in a way that was generally attributed to royalty. It was also said that the soul of Zarathustra was placed inside the sacred Haoma plant by God and he was conceived through the essence of Haoma in milk. Although some claim this would seem to imply some sort of “immaculate conception”, his parents are also acknowledged as “natural and earthly”. Zoroaster was also said to have laughed upon his birth instead of the typical newborn wail. As an infant, he glowed so brightly that the others who lived in his village feared him and attempted to hurt and even kill him, thinking him to be related to some sort of demonic spirit. But any and all attempts to harm the infant Zarathustra failed. It was said that he was unable to be burned by fire and that he was found unharmed after being stampeded upon by oxen and, in a separate event, horses. When he found himself alone in the wilderness, a mother wolf cared for him, even finding a sheep for the infant to suckle at, until he was reunited with his family.

Although it is true that most of those living in that area of Persia at that time were nomadic, Zoroaster’s extensive traveling throughout the Middle East (as extensively as one could during those times) was considered remarkable, and as a result, he was mentioned frequently in oral tradition throughout the region. In some scholarly texts, it is suggested that the division in religions in this region began when some nomadic societies began to take root and settle down into agricultural communities, while others found this new “settled” way of life unacceptable, even contemptible. Those who adhered to the nomadic tradition began to see these new settlements and their inhabitants as evil and in opposition to their own, and soon began to assign evil to not just the settlers, but to the things they did, the foods they ate, etc. Some have asserted that it was this split from which the Zoroastrian ideology of good vs. evil may have sprung, although there are likely many other social and political issues as well.

The Gathas comprise seventeen hymns —sometimes described as poems–written in ancient Iranian meter, and are believed to have been composed by Zarathustra himself. The purpose of the Gathas was to evangelize to the people of the world the truths revealed by Ahura Mazda to Zarathustra. These 17 hymns (also referred to as Hati, Haiti, or later, HAs) are made up of 238 stanzas (6000 words in total) and were later divided into separate chapters, or “Yasnas” as follows:

Yasna 28-34, Gatha Ahunavaiti (Song of the Lord), 100 stanzas, 3 verses

Yasna 43-46, Gatha Ushtavaiti (Song of Happiness) 66 stanzas

Yasna 47-50, Gatha Spenta Mainyu (Song of the Beneficent Spirit or the Holy Spirit of Good) 41 verses

Yasna 51, Gatha Vohu Khshathra (Song of the Good Domain or Realm) 22 stanzas

Yasna 53, Gatha Vahishto Ishti (Song of the More Desired or Loved) 9 verses

Throughout the Gathas, Zoroaster is addressing Ahura Mazda, the “Omniscient Creator” referred to at different times by the names Ormuzd, Ohrmazd, Hourmazd, Hormazd, and Hurmuz. Ahura Mazda is also sometimes referred to as simply “Lord” or “Spirit”. He is the first spirit who is addressed in the Gathas, as well as the spirit who is referred to most frequently.

Zoroastrianism is, at its core, the belief that good will conquer evil. The God of Life vs. the God of Death. Those who do good deeds, think good thoughts and limit their exposure to only “good” things promote Ormuzd—God of Life. Those who allow themselves to be involved with bad things, thoughts, or deeds give more power to Ahriman—the God of Death. From the Gathas: “Ormuzd was glorious with light, pure, fragrant, beneficent, daring, all that is pure. Then looking beneath him he perceived, at the distance of ninety-six thousand parasangs, Ahriman, who was black, covered with mud and rottenness, and doing evil. Ormuzd was astonished at the frightful air of his enemy. He thought within himself, ‘I must cause the enemy to disappear from the midst of things.’”

While the concept of good vs. evil seems simple enough as an ideology, the religion founded by Zarathustra goes much further and includes not only good deeds versus evil deeds, but the categorization of all things—both living and not—as either good or evil. By extension, humanity’s involvement with each thing (or being) can be counted as either promoting evil and darkness in the world, referred to as druj, and therefore championing Ahriman, the God of Death, or as engagement with only things and people which are associated with goodness, also known as Asha, resulting in the advancement of Ormuzd, Omniscient Creator. Alliance with one results in the direct deterioration of the other.

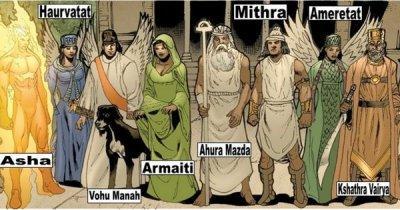

To this day, Zoroastrians repeat the tenets inherent to their religion. The law of Asha requires them to be guided by three fundamental precepts: Good thoughts (Humata), good words (Hukhta), and good deeds (Huvarshta). Emulation of the six holy councilors, or Amesha Spentas (literally, Bounteous Immortals), is the goal of the followers of Zarathustra. The Amesha Spentas are considered emanations of Ormuzd, and each one epitomizes a value or gift that humans must seek to possess. The six Amesha Spentas, also referred to as “divine sparks” or archangels which appear in Yasna 47.1 are listed below, followed by their traits or the virtues they represent:

Vohu Manah: “Good Mind/Purpose” Spirit of divine wisdom, light, and love

Asha Vahishta: “Excellent Order”, or “Truth” Spirit of Fire and Providence

Khshathra Vairya: “Desirable Dominion” Spirit of Power and Metal

Spenta Armaiti: “Beneficent Devotion” Spirit of Faith and Devotion

Haurvatāt: “Wholeness or Perfection” Spirit of Water and Plants, and

sister of

Amərətāt: “Immortality” Spirit of Water and Plants

These six divine sparks (sometimes referred to as archangels), of which three are male and three are female (Armaiti, Haurvatat, and Ameretat are most frequently regarded as female, and Vohu Manah, Asha, and Khshathra are generally considered male) emanated from Ormuzd with the purpose of assisting him in leading his people always and only towards good.

Zarathustra’s time of enlightenment is reported to have begun at the age of thirty. The legend says that when Zoroaster went to a river in order to fetch water that was required for a holy ritual, he was led to the presence of Ahura Mazda, “Omniscient Creator”, who instructed him in the basic tenets and foundations of the Good Religion. Zoroaster interpreted this meeting as a sign that he would be the new prophet and evangelizer of this new religion, and it would become his vocation to inform others of the new ideology, later termed, “Zoroastrianism”.

He preached that Ahura Mazda–Ahura is translated as “light” and Mazda as “wisdom” –was the very source of all goodness who created spirits (called yazatas) to assist him in the conquering of good over evil. Zoroaster informed his followers to beware of daevas (not to be confused with the devas of Indian religions). These daevas, or false gods, were no longer to be worshipped as they previously had been, as it was now known that they were created by Angra Mainyu, considered to be the root of all evil and sin in the world, for the purpose of tempting humankind with evil thoughts and deeds under the guise of godliness. Zoroaster did not describe Ahura Mazda as an all-powerful entity, but rather as a god who required the assistance of humanity in order to battle evil or Angra Mainyu, sometimes also referred to by the name Ahriman, or God of Death. This is an important distinction from the omnipotent Gods of other religions.

After Zoroaster experienced this enlightenment, he continued his travels through the Middle East, this time attempting to evangelize the philosophy which he and his followers had newly adopted, but at some point went through a period of feeling lost and unfocused. He was wandering with his followers and wrote the following after being cast out of his home, as written in Yasna 46 of the Zend-Avesta, which begins thusly: “To what land should I turn? Where should I turn to go? They hold me back from folk and friends. Neither the community I follow pleases me, nor do the wrongful rulers of the land… I know… that I am powerless. I have a few cattle and also a few men.” (Jafarey translation) At some point during his travels, he was granted an audience with King Vishtaspa. Many of King Vishtaspa’s priests and wise men were present during this assembly which lasted for three days. During the mostly-hostile debate, they asked him myriad questions about his new ideology before finally advising King Vishtaspa to imprison him and reject his ideas. The mythology of what happened next is not widely accounted for but in some versions, it is said that after King Vishtaspa’s favorite horse fell ill and became paralyzed,

Zoroaster proposed to King Vishtaspa that he would cure one of the horse’s legs for each of four requests the King agreed to fulfill for him. The first requirement was that King Vishtaspa adopt the ideologies of Zoroaster, the second and third, that his son and wife, respectively, also convert to Zoroaster’s philosophy, and, to cure the last of the horse’s legs, the men who had advised King Vishtaspa to imprison Zoroaster would have to be put to death. King Vishtaspa agreed and once all four conditions were met, the horse rose on his four legs and was cured. King Vishtaspa asked Zarathustra to reciprocate and to make the fulfill four requests of his own to him, now that the King had fully converted to Zoroastrianism. Firstly, that he would be able to see into the future to know fully where he would be when he finally moved on to the next world. The second was to make himself unassailable. The third request was that he would be able to see all that was to come in the future and the fourth that his spirit remain with his body until it was resurrected into the next world. Zoroaster demurred, and told King Vishtaspa that these four wishes were too much to be granted unto one man, and asked the king to choose just one of these. After King Vishtaspa decided that his most personally important desire was to see what his surroundings would look like once his soul had resurrected upon his arrival in the next world, Zarathustra gave him some holy wine. King Vishtaspa, entranced, sees himself in heaven amidst the glory of God. Once he had decided to espouse this new ideology, he enthusiastically encouraged his subjects to embrace it as well. Zarathustra’s relationship with King Vishtaspa, whose importance cannot be understated in the emergence of Zarathustra as a leader and prophet, would be the beginning of the widespread acceptance of Zoroastrianism as a new religion. King Vishtaspa and Zarathustra’s relationship seems to have been somewhat complicated, as the king is referred to at times (depending on the source) alternatively as Zoroaster’s follower, ally, and patron. During his time at the court of King Vishtaspa, which by most accounts lasted approximately three decades, he met and took on three wives, the last of whom was Hvovi, meaning Good Cattle. Hvovi, importantly, was the daughter of the prime minister of King Vishtaspa. As a result of this union, Zarathustra was now married into the king’s court, which caused him to become more and more historically important and prominent. During this time, he wrote the Gathas, and the names of King Vishtaspa and his court are included in parts of the Gathas, which are considered to be the holiest and sacred texts of the Zoroastrian faith, aka Zoroastrianism.

Zarathustra’s time of enlightenment is reported to have begun at the age of thirty. The legend says that when Zoroaster went to a river in order to fetch water that was required for a holy ritual, he was led to the presence of Ahura Mazda, “Omniscient Creator”, who instructed him in the basic tenets and foundations of the Good Religion. Zoroaster interpreted this meeting as a sign that he would be the new prophet and evangelizer of this new religion, and it would become his vocation to inform others of the new ideology, later termed, “Zoroastrianism”.

He preached that Ahura Mazda–Ahura is translated as “light” and Mazda as “wisdom” –was the very source of all goodness who created spirits (called yazatas) to assist him in the conquering of good over evil. Zoroaster informed his followers to beware of daevas (not to be confused with the devas of Indian religions). These daevas, or false gods, were no longer to be worshipped as they previously had been, as it was now known that they were created by Angra Mainyu, considered to be the root of all evil and sin in the world, for the purpose of tempting humankind with evil thoughts and deeds under the guise of godliness. Zoroaster did not describe Ahura Mazda as an all-powerful entity, but rather as a god who required the assistance of humanity in order to battle evil or Angra Mainyu, sometimes also referred to by the name Ahriman, or God of Death. This is an important distinction from the omnipotent Gods of other religions.

There is much speculation about the similarities noted between Zoroastrianism and other religions. Between Zoroastrianism and Judaism, similarities include but are not limited to the existence of six holy councilors, found in the part of the Gathas called the Vendidad, which has been compared to Moses’ Pentateuch, or Torah. Another commonality is noted in the way both Ormuzd and Ahriman oversee a council of six, which is also found in the Talmud. There is also a school of thought which attributes the origins of Christianity to 500 years of the concurrently existing ideologies of Zoroastrianism and Judaism. In fact, all three religions share a number of similar dogmas. They all have a belief in one God (monotheism) and agree about the existence of Heaven. All three ideologies require a strong code of ethics from their followers and believe that we will all be judged individually one day. Similarities also exist in the concept of a Messiah that will one day come to join humans on earth to bring them to ultimate spiritual renewal and eternal peace, and all three share the goal as the eventual conquering of “Evil”, with “Good” claiming final victory.

The first evidence of this intermingling of ideologies shows itself when Cyrus the Great triumphed over the Assyrians and the Jewish people were released after years of captivity by the Babylonians. As noted frequently in the Old Testament, Cyrus, the Persian Emperor, was declared not only their liberator but their Savior, and frequent mention is made throughout the Old Testament of his fellow Iranian rulers, Xerxes and Darius.

While Jesus was born via Immaculate Conception to an earthly mother, Zarathustra wrote of his Savior being born to a mother who, at least during her pregnancy with Ahura Mazda, the Omnipotent Creator of Zoroastrianism, was possessed of divine qualities. The date on which the birth of the Christian Savior is celebrated most widely is December 25th. This date is also the date on which the Roman festival of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (otherwise known as the birthday of the sun) is celebrated. It is thusly called because it is the first day following the Winter Solstice when the sun is “reborn” and shows itself for longer periods each day. It was not until 345 A.D. that this date was associated with the birth of Jesus, some say as a reminder of the presence of Christ as the light in our lives.

Fire is certainly the most important symbol of the Zoroastrian faith, as it symbolizes so many things which are central to its ideology. Fire allows us to cook food so we remain strong and in good health. When homes were less secure and most residences were tents or huts, the fire would act as protection from wild animals. It also has more metaphysical properties. In the Gathas, Yasna 31.3, Zarathustra says, “The happiness You grant has been promised… through Your mental fire and righteousness.” (Ali Jafarey translation). In other words, “mental fire” refers to the enlightenment of the mind and the brightening and stimulation of the intellect via the acceptance and exaltation of Asha (goodness).

Sacred fires have long been a part of the Zoroastrian faith, and remain so today throughout the world. There are considered to be three classifications of consecrated fires which millennia ago were associated with different tiers of society. It is vital that the holy fires be kept pure and unadulterated by humans or animals, and its use must be reserved solely for sacred purposes. In other words, it must not be used for heating a home or cooking food, for then it becomes impure and is no longer considered holy.

The most modest and most common of Zoroastrian fires is The Atash Dadgah, which refers to the daitya gatu (Avestan for appointed place). This sacred fire may be burned in any unsullied location, including homes or community centers. It is also the fire used in ceremonies, rituals, and celebrations, and is not meant to be kept enkindled eternally, but is allowed to burn out on its own. Any attempt to blow out or extinguish the fire is considered irreverent as it should never be touched by human flesh or even human breath. Zoroastrian priests who lead rituals or pray at the fireside are required to don a face mask with the explicit purpose of disallowing his breath or saliva to come in contact with the fire, as both of these are seen as unsanctified by followers of Zarathustra.

A higher grade of Zoroastrian fire is known as the Adur Aduran, meaning “fire of fires”. It is so called because it unites the community, which is generally made up of different tiers or classes of society, through the practice of having them each bring embers from their own fires to be united into one holy community fire. It is this category of fire which is to remain burning constantly, or, at a bare minimum, smoldering. A contingent of priests is charged with maintaining the flames by attending to it a minimum of five times daily, adding wood and/or oils—typically sandalwood–as necessary.

Atash Bahram is the paramount level of fire and is the fire of the aristocracy and nobility. Its name literally means fire of victory. Although the precise origination of this title is unknown, it is theorized that the symbolism refers to the victory of good over evil. The preparation of this sacred fire, and the consecration rituals required to create it can take up to one year to complete. 32 Zoroastrian priests are called upon to take part in the ceremony, which entails the gathering of sixteen different types of fire, each of which must be purified individually. The different types of fires include lightning, fire from a cremation, and embers which have been brought from the fires used by a number of different societal vocations such as blacksmiths, potters, hunters, etc., among other sources. The priests are then called upon to maintain the fire continuously.

There currently remain ten Atash Bahrams (sometimes referred to as Atash Behrams) with eight continuously burning in India and two in Iran. These fire temples are made available solely to practitioners of the Zoroastrian faith, and entrance to non-followers is strictly forbidden. The Atash Bahrams are kept very simple in their décor, without adornment or ornamentation; the fire itself is the focal point, although in a separate room from where the disciples are permitted to gather and worship.

Fire is also an important component in Zoroastrian homes and serves as the focus of attention during prayers. The fire can be something as small as a prayer-time-devoted candle, although the fire itself is never worshiped directly. Zoroastrians may also choose to simply face a light source (natural light sources are most preferable) in the absence of fire. The idea that Zoroastrians worship fire is a total misconception, and fires are primarily used to maintain the focus on the basic principles of Zarathustra during prayer: good over evil–maintaining good thoughts, good words, and good deeds. Fire represents enlightenment, while darkness represents evil. Put most plainly, the absence of light is darkness, just as the absence of good is evil.

Few Christians are aware that the trio known as “The Magi”, “The Three Wise Men”, or “Three Kings” are actually a group of Zoroastrian priests. (Who knew that there would be figurines of Zoroastrian Priests displayed in the nativity sets of almost every Christian home every Christmas?) In Matthew 2, New King James Version, the “wise men from the East” was actually a translation of the Greek, “Magoi”, which referred specifically to a tribe of Zoroastrian priests. There is no mention elsewhere of any “wise men” or “kings” in Matthew or any other biblical stories detailing the description of Jesus’ birth. The magi, which means magnanimous or generous, is the word from which the English words “magic” and “magician” were both derived, although they were no more magicians than our modern day scientists are. These Zoroastrian “wise men” were practitioners of science and astronomy, which at that time were just beginning to be studied and understood. As such, they were knowledgeable about principles and ideas as yet unknown to most.

These nomadic followers of Zarathustra, according to the Christian Bible, were the “wise men” who told King Herod they had heard about the new “King of the Jews” who had been born under a star and they had come from The East “to worship Him”. King Herod chose the Zoroastrian priests to verify the authenticity of this new “King”, sending them on what was essentially a fact-finding mission.

From Matthew 2:

“When they heard the king, they departed; and behold, the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came and stood over where the young Child was. 10 When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceedingly great joy. 11 And when they had come into the house, they saw the young Child with Mary His mother, and fell down and worshiped Him. And when they had opened their treasures, they presented gifts to Him: gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

12 Then, being divinely warned in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they departed for their own country another way.”

The Magi brought to the new “King of the Jews” gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh (the latter two are still offerings made in Zoroastrian temples). Zoroastrian Fire Temples (or put more plainly by many followers of Zarathushtra, fire houses), contain a constantly-burning frankincense and sandalwood oil-fueled flame which is said to be symbolic of purity and truth. Because it burns straight upward, with the smoke rising, it has no chance of being polluted. The flame is considered a representative of Ahura Mazda (along with all other natural light sources including the sun and stars), and the most important source of life which provides all of humanity with life and warmth.

While Christians are said to maintain the belief that one’s body is a temple, Zoroastrians maintain that one’s life is the “temple” of his soul. Living a life which fulfills the Zoroastrian principles is the exhibition of a person’s beliefs. Making declarations of faith and spending time reciting prayers, while encouraged five times daily, are considered much less important in the practice of “living one’s faith” than acting on the ideology of good thoughts, good words, and good deeds, with prayer serving as a reinforcement or proclamation of those beliefs. Many Zoroastrians choose to keep their heads covered during prayer.

Followers of Zarathustra also employ the recitation of mantras (or manthras) as a mode of prayer. Some examples of Zoroastrian mantras, translated from the Avestan in the Gathas are:

“Every good thought every good word every good deed is of wisdom born

Every evil thought every evil word every evil deed is not of wisdom born

Every good thought every good word every good deed leads to the best existence

Every evil thought every evil word every evil deed leads to the worst life

Every good thought every good word every good deed is the best existence

That which is begotten of righteous order”

For followers of Zarathustra, the goal in the recitation of mantras might be introspection and the reaffirmation of one’s faith. Proclaiming the mantras can also be seen as a form of meditation. It is said that even when the reciter does not fully understand the words which he is speaking, the result of verbalizing the mantras is the calming of one’s spirit and the clearing and/or focusing of one’s mind, a process which is vital in the quest for enlightenment.

Another element which is vital to Zarathustra’s followers is water, which, along with fire, is considered a principal component of purification, which is necessary for aligning oneself with Ahura Mazda—the ultimate goal for the followers of Zarathushtra. In the Gathas, Yasna 38.3 refers to water as “glowing, resplendent, and divine.” In another passage, waters are referred to as the “mother of life”. Ahura Mazda revealed himself to Zoroaster when he was fetching water needed for a sacred ritual, and offerings of holy water were frequently referred to in later writings about Zarathustra, including in Zadspram 21.1, a 9th-century Zoroastrian scholar.

As with fire, it is considered disrespectful to allow a water source to become polluted. Sullying a water source with such impurities as urine, saliva, or the bodies of the dead is disallowed. Even drops of dew were considered sacred and representative of water as a whole by Ancient Persians and garnered their respect. Purification rituals are painstaking and lengthy, with the end goal, always, of maintaining them unadulterated and life-giving. The sanctification of water is referred to in Yasna 63-69 as “the invocations to the waters”, and is central to a Yasna service, along with prayers to fire. Arrangements for the creation of holy water must only happen between the time between sunrise and noon, and should never be offered—or even obtained from a water source–at night, due to its sacred nature.

When ingested, holy water is said to have curative properties, although only a sip is needed. The remaining water must be spilled upon the roots of certain vegetation, in particular trees which bear fruit. It was considered beneficial for soldiers who were setting off for warfare to spill onto the battlefield an offering of holy water before departing, ensuring their safe return.

It is requisite that fire temples are constructed close to a water source such as a stream or well, and holy water is poured in a three-part ritual into a spring or other water source whilst reciting the Avesta. The Zoroastrian philosophy behind the holy water ritual is that through the offering of the holy water made to the water source, the water source itself becomes stronger, more voluminous and life-giving.

It is always considered preferable to meditate or worship near water sources, and many Zoroastrians make pilgrimages to oceans, seas, rivers, and waterfalls on the tenth day of the month with the intention of making offerings to the waters. Offerings to waters are still made by orthodox Zoroastrians. A commonly-offered concoction consists of a mixture of milk and two plant-derived ingredients, such as rose petals, leaves of marjoram, or the fruit of certain trees. After the mélange has been ritualistically prepared, it is brought with much veneration to a Zoroastrian priest. Once the priest has transported the liquid mixture to the waterfront, it is methodically, spoonful-by-spoonful, offered into the body of water while prayers are recited. This ritual is performed in Orthodox communities by Zarathustra’s devotees twice yearly.

Purity is a vital theme throughout Zoroastrian practices and beliefs and even extends to the rituals through which death and funeral practices are handled. The second a body is devoid of life, it is believed that decomposition has already begun to set in, and the body of the dead is now considered impure or “druj”. Great pains are taken to avoid coming into direct physical contact with the corpse, and even those tasked with preparing a body after death are careful not to touch it with bare hands, using instead hooks and other instruments to remove clothing from the body to prepare it for its final resting place. The decomposition, believed to be the work of Druj-Nasush, also known as the “corpse demon”, is considered communicable, and must be avoided at all costs. Contact with any sort of environmental corruption provokes a similar scourge upon the purity of one’s spirit. Maintaining the remaining community’s distance from the corpse is vital in securing its spiritual purity, and priests are called in as soon as death is thought to be imminent with the intent to minimize and contain the effects of any potential contamination.

The priests prepare the body through washing it in unconsecrated bull’s urine, called “gomez”, and water. This is done in a room that has been cleaned especially in preparation for the body, and a set of clothing is freshly cleaned in which the body will be clothed after the ritual cleansing is complete. After the body has been cleaned and is dressed and laid upon a clean white sheet, a viewing is held for loved ones who wish to say their final farewells. Physical contact with the corpse is, again, considered absolutely forbidden.

As the body is now considered impure, a custom called “Sagdid”, roughly translated as “dog sight or gaze” is performed. Sagdid is the ritual in which a dog, most preferably a “four-eyed” dog (this title is believed to refer to a dog with two spots or flecks over its eyes) although any dog would do if a “four-eyed” dog is unavailable, is brought in the room of the dead to gaze upon the body. Different sources speculate alternative reasons for the performance of this ancient Zoroastrian ritual. One theory is that the dog would be able to determine whether or not the person was definitively dead, and not merely comatose, and that the dog’s actions toward the body would indicate if the funeral process should be continued. Alternatively, it is speculated that the very presence of the dog in the room with the now decomposing body would assist in warding off any demonic presence.

“You shall, therefore, cause the yellow dog with four eyes, or the white dog with yellow ears, to go three times through that way. When either the yellow dog with four eyes, or the white dog with yellow ears, is brought there, then the Druj Nasu flies away to the regions of the north, in the shape of a raging fly, with knees and tail sticking out, all stained with stains, and like unto the foulest Khrafstras[4]”

— The Vendidad, Fargard VIII, Verse 16

A fire, which also aids in the purification of the atmosphere, is also customarily present during the Zoroastrian funeral ritual and is fed continuously with oils of sandalwood and frankincense in an effort to keep contamination of the living at bay. It is also common to draw a circle around the area where the corpse is laid out in order to make callers aware that the body of the deceased is present and they should maintain a safe distance to avoid corrupting themselves with the druj from the corpse.

The cadaver generally remains in the visitation room for a period of 24 hours, after which it is transported to its final resting place. This transfer must take place during daylight hours, and pairs (even numbers only) of “corpse-bearers” are required to move the body to the “dakhma”, or funerary tower. Such towers are also called “Towers of Silence” and are built out of either stone or brick at a height reaching about eight meters, or approximately 25 feet. The clothing and white sheet, which has been wrapped– shroud-like–around the body, are then removed–again using instruments to avoid contamination. The clothing and sheets are subsequently disposed of in a way that ensures they can never be used or come in contact with again.

Finally, the corpse is laid upon the zenith of the funerary tower atop grates which allow for complete disposal of the body, for after birds of prey have had a chance to clean the bones of all flesh, the remaining bones fall through the grates into a pit. These pits are built specifically for the purpose of collecting the parts of the corpse which remain after the birds of prey have had a chance to indulge in their funeral feast, a procedure which generally takes only the better part of the afternoon. These processes allow Zoroastrians to ensure that the body comes into contact with neither fire (as would occur in cremation) nor earth (where one would be interred in a burial) which would compromise the Zoroastrian belief that the now decomposing corpse would compromise the purity of either ground or flame.

After prayers are said by (usually) two priests, final respects are paid to the body before the attendees cleanse themselves with water and gomez. This additional purification ritual done by the followers of Zarathustra was done with the intent of helping to sanitize themselves as much as possible before returning home from the funeral. This is followed by additional bathing upon arrival at their residences, with the objective of preventing any possible contamination they may have encountered, despite their elaborate care-taking, the opportunity to enter into their homes.

Although the Zoroastrian funeral process is now complete, there are still rituals that must be performed. Three days of intermittent prayers are said for the departed one, a time period during which it is believed that the soul has not yet departed from its earthly home. During this three-day mourning period, meat is generally avoided completely, as is cooking within the four walls of the home in which the corpse-cleansing rituals were prepared. Meals are instead prepared by friends of the family of the deceased and brought to them. A fire is lit and maintained for three days in winter, or ten days in the summer. Traditionally, a lamp is also kept lit during this time.

After the third day, Zarathustra’s followers believe that the soul is escorted by its “fravashi” or spiritual guardian up to Chinvat, “Bridge of the Requiter” which separates the worlds of the living and the dead. It is also referred to as the “Sifting Bridge” upon which all ascended souls must tread. It is on this bridge, which is guarded by two four-eyed dogs, that one meets his fate, determined by his actions on earth. For those followers of Zarathustra who have lived a life of Asha: good thoughts, good words, and good deeds, the bridge they encounter will be wide and roomy, and they will be led by the Daena, who is described at times as the “religious conscience” as well as the most beautiful of all women, to the “House of Song” which is the paradise where they will be met by Ahura Mazda. Chinvat, The Bridge of the Requiter, has been affiliated with rainbows as well as with the galaxy of The Milky Way, although this concept is also disputed by some Zoroastrians.

Those who have led lives which were more affiliated with druj or evil are instead greeted with a bridge that is narrow and treacherous and will soon be led by a demon, “Vizaresh” to the “House of Lies”, a place of continual and eternal torment and misery. The Zoroastrian concepts of the Houses of Lies and Song are certainly similar to the Christian after-life philosophies of Heaven and Hell.

Present-day followers of Zarathustra number an estimated 200,000 – 250,000 across the world, although the highest concentration is in India (mostly in Mumbai) where they are also called Parsis, due to their immigration from Persia, from which they fled between the 7th and10th centuries, depending on the source, in order to avoid religious persecution by the Muslim community. The modern-day Zoroastrians have a reputation as good and honest people, who are sought-after in business and financial dealings. They have contributed significantly to the Indian population in ways both financial and historical, making donations which changed the landscape of their country as well as assisting in the foundation of the Indian Nationalist movement.

Modern practice for followers of Zarathustra, along with the practices previously described above, includes the daily recitation of The Zoroastrian Creed. The following is an excerpt:

1.) I curse the Daevas. I declare myself a Mazda-worshipper, a supporter of Zarathushtra, hostile to the Daevas, fond of Ahura’s teaching, a praiser of the Amesha Spentas, a worshipper of the Amesha Spentas. I ascribe all good to Ahura Mazda, and all the best, the Asha-owning one, splendid, xwarena-owning, whose is the cow, whose is Asha, whose is the light, ‘may whose blissful areas be filled with light’

2.) I choose the good Spenta Armaiti (Holy Spirit) for myself; let her be mine. I renounce the theft and robbery of the cow, and the damaging and plundering of the Mazdayasnian settlements.3.)

3.) I want freedom of movement and freedom of dwelling for those with homesteads, to those who dwell upon this earth with their cattle. With reverence for Asha, and (offerings) offered up, I vow this: I shall nevermore damage or plunder the Mazdayasnian settlements, even if I have to risk life and limb.

4.) I reject the authority of the Daevas, the wicked, no-good, lawless, evil-knowing, the most druj-like of beings, the foulest of beings, the most damaging of beings. I reject the Daevas and their comrades, I reject the demons (yatu) and their comrades; I reject any who harm beings. I reject them with my thoughts, words, and deeds. I reject them publicly. Even as I reject the head (authorities), so too do I reject the hostile followers of the druj.

5.) As Ahura Mazda taught Zarathushtra at all discussions, at all meetings, at which Mazda and Zarathushtra conversed;

6.) As Ahura Mazda taught Zarathushtra at all discussions, at all meetings, at which Mazda and Zarathushtra conversed — even as Zarathushtra rejected the authority of the Daevas, so I also reject, as Mazda-worshipper and supporter of Zarathushtra, the authority of the Daevas, even as he, the Asha-owning Zarathushtra, has rejected them.

6.) As the belief of the waters, the belief of the plants, the belief of the well-made (Original) Cow; as the belief of Ahura Mazda who created the cow and the Asha-owning Man; as the belief of Zarathushtra, the belief of Kavi Vishtaspa, the belief of both Frashaostra and Jamaspa; as the belief of each of the Saoshyants (saviors) — fulfilling destiny and Asha-owning — so I am a Mazda-worshipper of this belief and teaching.

7.) I profess myself a Mazda-worshipper, a Zoroastrian, having vowed it and professed it. I pledge myself to the well-thought thought, I pledge myself to the well-spoken word, I pledge myself to the well-done action.

8.) I pledge myself to the Mazdayasnian religion, which causes the attack to be put off and weapons put down; which upholds khvaetvadatha (kin-marriage), which possesses Asha; which of all religions that exist or shall be, is the greatest, the best, and the most beautiful: Ahuric, Zoroastrian. I ascribe all good to Ahura Mazda. This is the creed of the Mazdayasnian religion.

From the E-Book, “Who Was Zoroaster?” © 2017 5th Dimensional Quantum Healing & Awareness by Author: Roisin Herrera